One of the almost inevitable consequences of using Arch Linux for any length of

time is that you will find yourself, if you weren’t already, sucked into the

gravitational vortex of the command line. The drive to continually understand,

refine and customize your setup, your workflow and the tools you use on a daily

basis will surely lead you to the point where you go from having one of those

dinky terminal emulators that scrolls down when you hit F12, to waking

up one day after yet another sleepless night trying to get your head around

C or

Haskell—so that

you can hack your tiling window manager to manage the dozen or so terminals

you constantly have open to your increasingly exacting specifications…

One of the almost inevitable consequences of using Arch Linux for any length of

time is that you will find yourself, if you weren’t already, sucked into the

gravitational vortex of the command line. The drive to continually understand,

refine and customize your setup, your workflow and the tools you use on a daily

basis will surely lead you to the point where you go from having one of those

dinky terminal emulators that scrolls down when you hit F12, to waking

up one day after yet another sleepless night trying to get your head around

C or

Haskell—so that

you can hack your tiling window manager to manage the dozen or so terminals

you constantly have open to your increasingly exacting specifications…

Once you resign yourself to this inevitability, it is a natural progression to

invest some time in setting up your terminal so that it is a pleasant, productive

environment. The first step is to choose your terminal emulator. After playing

with a few, I have settled on

rxvt-unicode.

Urxvt has a number of nice features, principally the ability to run in daemon

mode and, when combined with Bert Münnich’s

urxvt-perls extension,

to be able to interact with text and URLs

with the keyboard.

I have also, over the last two or three months, been intermittently using

termite; the VTE-based

terminal developed by

Daniel Micay and

Simon Gomizelj.

The next step is to select a colour scheme that, after long hours of peering at

the screen, won’t leave you with the eyesight of a mediæval monk. I have settled

on a dark scheme that is relatively low contrast, so works well in natural and

artificial light.1 Combine this with a

custom Vim colourscheme

for syntax highlighting, and you have the base for a consistent aesthetic

experience in your terms.

The cornucopia of choice that is GNU/Linux means that in addition to choosing

your font, you also can choose how it is rendered. I use the

infinality patchset,

but if you are looking for a pre-rolled version I can highly recommend

bohoomil’s

infinality bundle.

The final element—and probably the most important—is the actual shell that you

will run in your terminals.

Bash is installed

everywhere (or, more correctly, everywhere that matters), so that is a solid choice.

If you are looking for a lot more power and flexibility, then you want

Zsh (with the

syntax highlights

plugin).

If, on the other hand, you are the sort of person with tribal piercings

and a fixie, you might want to look at

tcsh, or even

csh2.

Customizing your shell can, in this context, be extended to practically Escheresque

extremes. The prompt, particularly in Zsh, can print relevant information,

helpfully colour coded; but it can also metastasize into a bloated ratmangle of

unicode, complete with git branches, the weather in four different timezones and

random fortunes.

If, through some inexplicable turn of events, you find yourself staring at

something like this, it is time to seek help. Urgently.

For Zsh, I have the hostname (to avoid confusion when SSH'ing between machines,

the current working directory and, if the exit status is anything other than 0

for the last command, that status is appended.

There is one other important choice to make in your shell: to run it in emacs

mode (the default) or vi-mode. This decision says as much about your competence

as it does about your overall contribution to the gene pool, so consider it carefully.

I have previously expressed my

preference for vi-mode,

and using Zsh (which doesn’t use readline) has just entrenched that view for me.

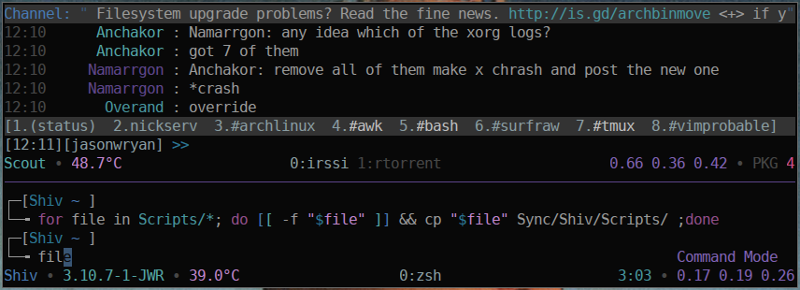

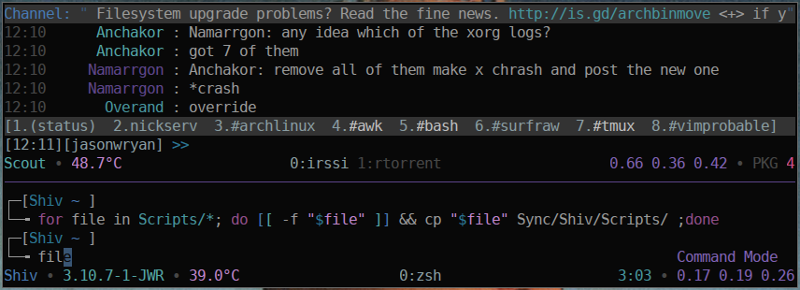

Putting it all together, you end up with an interface that is as attractive to

work with as it is powerful. You have syntax highlighting, command completion

(and with Zsh, impressive correction), coloured URLs that

can be activated with the keyboard, the ability to copy and paste between

terminals and into documents or browsers, configurable keybinds, aliases and

functions limited only by your imagination and the threshold of your indolence.

One final recommendation: consider using a terminal multiplexer like tmux to

manage your terminal sessions. I have posted quite a bit about it

in the past and it

continues to be a mainstay of my working environment. The

Arch Wiki, naturally,

has some very detailed pages on each and every aspect of using the terminal.

All of my configs are available in my bitbucket repositories:

bitbucket.jasonwryan.com.

Notes

- My dark colour scheme is in my

bitbucket repo.

- Then again…

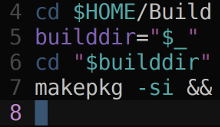

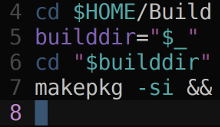

I posted a couple of weeks ago about

compiling a custom kernel

using modprobed_db

and at the time I talked about automating the process, essentially so that every

kernel update, be it the standard Arch kernel or the stripped down custom one,

would be a simple, streamlined process. I updated that post with

a PKGBUILD,

which was the first step. This completes that process.

I posted a couple of weeks ago about

compiling a custom kernel

using modprobed_db

and at the time I talked about automating the process, essentially so that every

kernel update, be it the standard Arch kernel or the stripped down custom one,

would be a simple, streamlined process. I updated that post with

a PKGBUILD,

which was the first step. This completes that process. One of the almost inevitable consequences of using Arch Linux for any length of

time is that you will find yourself, if you weren’t already, sucked into the

gravitational vortex of the command line. The drive to continually understand,

refine and customize your setup, your workflow and the tools you use on a daily

basis will surely lead you to the point where you go from having one of those

dinky terminal emulators that scrolls down when you hit F12, to waking

up one day after yet another sleepless night trying to get your head around

One of the almost inevitable consequences of using Arch Linux for any length of

time is that you will find yourself, if you weren’t already, sucked into the

gravitational vortex of the command line. The drive to continually understand,

refine and customize your setup, your workflow and the tools you use on a daily

basis will surely lead you to the point where you go from having one of those

dinky terminal emulators that scrolls down when you hit F12, to waking

up one day after yet another sleepless night trying to get your head around

While chasing edits on the Arch Wiki a couple of weeks ago, I stumbled upon

this page:

While chasing edits on the Arch Wiki a couple of weeks ago, I stumbled upon

this page: